Discussions about end-of-life have been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Are we ready to move towards real social transformation?

Five years ago today, on April 16 2015, I defended my Master of Design at OCAD University as part of the Strategic Foresight and Innovation program. I chose April 16 because it is National Advance Care Planning Day and it made sense that this would be the day to share my research on the experience of distanced family members during palliative care.

Since that time, I’ve continued to do work focussed on end-of-life. I have been using participatory design and art as a mechanism for exploring our individual and collective experiences and I have been collaborating with health care organizations and hospices on design solutions to enable conversations in the death and dying space. It’s an important topic and I believe deeply that designers are uniquely suited to contribute to the development of support and services for people at the end-of-life.

I believe this is even more true today as we find ourselves in the midst of a pandemic.

How the end-of-life discussion is changing.

As I look back on my research, I have been thinking a lot about how the themes that emerged have been impacted by COVID-19 and I have been drawn to consider:

- What has changed?

- What conditions have emerged?

- What has been accelerated?

One of the biggest questions I’ve been asked recently is about distance. One of my primary research questions was “How might we better meet the needs of family members who are at a distance during palliative care?”

“How might we better meet the needs of family members who are at a distance during palliative care?”

The catalyst for this framing was my own experience of being at distance when my dad was dying from cancer. At the time, distance was primarily framed as the geographic proximity between the person with a life-limiting illness and their distanced family member.

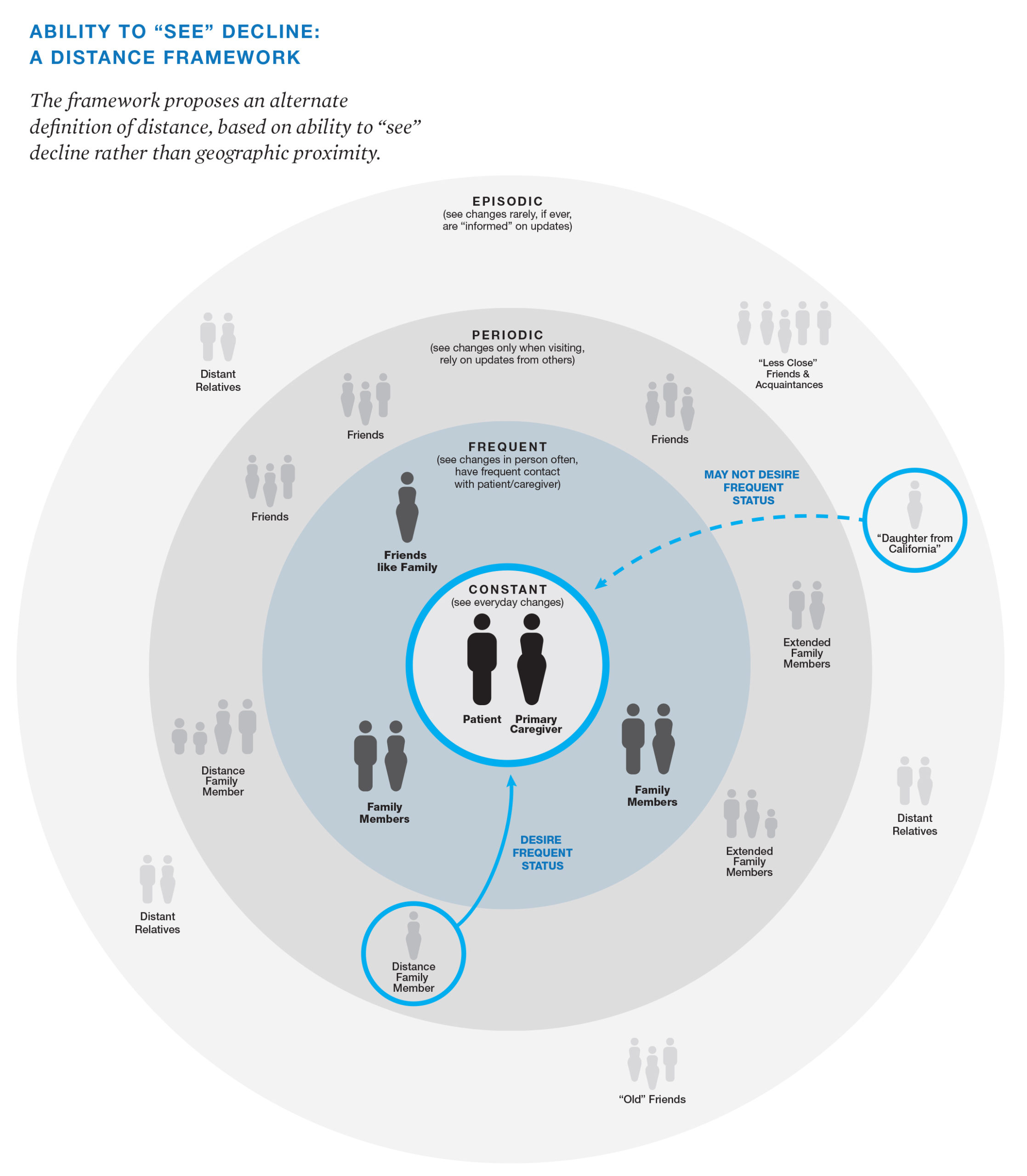

What emerged was an alternate definition of distance, based on the ability to “see” decline. This framework focused on the ability of a family member to “see” for themselves the condition of their loved one. How did they look? Were they able to eat? Were they mobile or unable to get out of bed? These signals of the human condition were described as critical signs for family members to understand the trajectory of decline. The better we are to see decline, the more prepared we are for discussing death and the dying process.

Illustration: Extracted from Bridging the Distance: Communicating to Distance Family Members during Palliative Care, 2015 by Karen Oikonen. The full research project can be read here.

As we all collectively work towards #flatteningthecurve, we are also all effectively at a distance. Distance makes everything related to end-of-life more difficult. Geographic distance is no longer the defining factor. It doesn’t matter if we live down the street, in the same city, or a few hours away‚ we cannot and should not, be seeing someone in person.

Those of us with family members in long-term care homes struggle with how to connect and it’s very difficult to “see” how they are doing. To “see” if they are safe. To make things more difficult, if our family member has an illness that impedes communicating on their own, such as dementia or stroke, it means we must depend on information from health care providers that are also in the midst of doing everything they possibly can to manage the virus but are also faced with limited space, staff, and supplies.

Families are wrestling with making decisions from afar, and anticipating decisions that have yet to be made—sometimes with limited information, limited sightlines into what’s happening, or simply no information at all. The prospect of someone we love dying in isolation is very real.

It’s heartbreaking and we’re scared.

How the pandemic is changing our perceptions on end-of-life.

In the midst of that fear and worry, there are also signals of hope. The COVID-19 pandemic is creating disruption across all aspects of our lives, which is also creating the conditions for new thinking and innovation.

Personalizing the impersonal.

I read an article that celebrated health care providers finding ways to make a human connection with COVID patients in emergency rooms by writing their names and taping photos of themselves to their PPE so patients could see the face behind the mask.

The COVID-19 pandemic is creating disruption across all aspects of our lives, which is also creating the conditions for new thinking and innovation.

Evolving processes.

As more and more Canadians look to put wills in place, in-person witnessing is no longer possible within the parameters of physical distancing. So the process is evolving. The emergence of ‘virtual witnessing’ of wills is helping to navigate estate law to enable the execution of wills online. Digital will service, Willful is leading the charge to meet the needs of Canadians who are creating wills from home and want to ensure they can be executed.

Enabling connection through digital touchpoints.

Health care organizations and long-term care homes are adopting technology in new ways to connect family members with residents to address isolation. When I was doing my Masters research in 2014-2015, I asked the clinicians I interviewed about using technology to connect distanced family members to their loved ones who were in palliative care. The question was often met with a list of reasons why it wasn’t possible.

One social worker reflected that the health care system would eventually get there as younger generations expect increasingly more access through digital channels. No one could have anticipated that a pandemic would force the adoption of technology to connect loved ones in dire situations. Seeing creative problem solving to bring families together is one of the positive outcomes of physical distancing.

These are just a few examples of how people across the end-of-life space are looking at, and developing solutions for, emerging challenges. I hope this type of thinking creates norms that stick in the future, rather than reverting back to our old pre-pandemic patterns and barriers.

From death-denying to death-discussing.

Let’s talk about a more systemic and challenging issue to tackle: the shift from a death-denying culture, to one that is death-discussing.

In 2013, the Vanier Institute of the Family published a report titled, “Death, Dying and Canadian Families,” which highlighted Canadians’ uncomfortable relationship with death. This was underpinned by a number of historical contexts that led to the “medicalization of death and dying” between the 1950s and 2000s that moved death into hospitals and away from the home. As advances in medicine progressed, we increasingly focused on curative measures and lost sight of the ability to have conversations about death and dying.

Organizations such as Death Café and Death over Dinner promote open conversations in non-medical environments.

Designers have taken up the challenge for how to support conversation about end-of-life by creating accessible games such as Hello by Common Practice.

Apps and online tools are helping us to think through our wishes for end-of-life, and they’re helping us plan and document our choices. Cake, The Conversation Project, and Everplans, are just a few examples. As preferences for everything from grocery shopping and buying our cell phone plans move online, end-of-life is no exception. These apps and online tools provide the public with an opportunity to plan on our own end-of-life choices, in our own time, rather than rely on facilitation from experts.

I’ve been lucky over the last few years to collaborate with my colleague and friend Kate Hale Wilkes on a number of projects related to end-of-life. Drawn together through our personal experiences of the death of a parent, we created Constellations to explore the family experience of end-of-life and exhibited at the DesignTO festival in 2019.

Constellations straddled the lines of participatory art and design, public engagement, and design research. Our hope was to prompt dialogue on this often avoided, yet universal experience. The goal was to move the topic of death and dying out of hushed conversation and into the public spotlight.

The result was a vast collection of experiences, a powerful indication that given the opportunity to engage on their own terms, people want to explore their experiences with death and dying, and in doing so, can feel less alone.

How will you respond?

In recent weeks, I have read article after article highlighting that it is more important than ever to have conversations about end-of-life with the people that matter most. We’re being encouraged to share our wishes, make our choices clear, and create the documents to enable our family members to follow those choices if needed.

As a human-centered designer and researcher, I look to my fellow designers to see this moment in time as the opening of a window for social transformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the importance of talking about end-of-life. I am hopeful that this global and collective experience will be the catalyst to shift us towards a death-discussing culture so that we are all better able to share what we hope for ourselves now and in the future.

As a human-centered designer and researcher, I look to my fellow designers to take up the challenge and to see this moment in time as the opening of a window for social transformation. It’s an invitation to lean in and to leverage our unique skills to create solutions for how we might support people when they are at their most vulnerable. This need won’t go away when we come out the other side of this pandemic.

By 2031, more than a quarter of Canada’s population will be over the age of 65. We have the opportunity to propel the shift forward and seek ways to create tools, services, supports, strategies, and policies that support people and their families—however we choose to define family—that is compassionate and human-centered, and honours what people wish for their end-of-life.

Today is April 16, 2020, National Advanced Care Planning Day. It’s a good day to think about your end-of-life wishes. It’s a good day to talk to those you love about their end-of-life wishes, too.

Let’s talk about death and dying.

Do you have questions about designing for end-of-life? Email me at karen@themoment.is. I am always happy to chat about how to approach challenges related to death and dying through the lens of design.

Resources

If you are looking for resources to begin thinking about an Advance Care Plan, Speak Up Canada and Dying with Dignity are places to start. If you’re looking for an accessible approach to creating a will, have a look at Willful.